Bill C-9 removes Attorney General consent

Dissecting the Combatting Hate Act: why Criminal Code changes meet provincial prosecution gatekeeping. This Record isolates the consent-removal mechanism, quantifies hate-crime volume, and stress-tests where enforcement clocks cannot be accelerated.

THE FACTS

Bill C-9’s short title is the Combatting Hate Act, as set out in the bill’s opening clause. The bill amends the Criminal Code by adding new indictable and hybrid offences related to hate-motivated conduct.

These new offences target intimidation or obstruction intended to prevent lawful access to specified places, including places of worship, educational institutions, and community centres.

The offences apply only where intent is established and where conduct occurs in proximity to the protected location, as prescribed in the bill text.

Bill C-9 removes the requirement for Attorney General consent before laying charges under the hate propaganda provisions of the Criminal Code.

Under the amended framework, charge approval proceeds through ordinary police investigation and provincial prosecutorial screening processes.

The bill codifies a statutory definition of “hatred”, intended to reflect the Supreme Court of Canada’s interpretation in prior Charter jurisprudence.

The Charter Statement accompanying the bill states that the definition is designed to preserve the existing high threshold distinguishing hatred from offensive or unpopular expression.

Bill C-9 also creates an offence for public display of specified hate or terrorist symbols when the display is intended to promote hatred against an identifiable group.

The Department of Justice stated in its official announcement that removing the consent requirement is intended to eliminate a procedural step in initiating prosecutions.

Statistics Canada recorded 4,882 police-reported hate crimes nationally in 2024. This followed 4,828 incidents reported in 2023, based on the same reporting methodology.

System Capacity Exposure

| System Edge | What Expands | Hard Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Police Intake Evidence-building | More complaints triaged as potential hate-motivated intimidation, obstruction, or propaganda. | Investigations require admissible proof of intent, identity, and context; file quality governs charges. |

| Crown Screening Charge approval | More files reviewed without the Attorney General consent gate for hate-propaganda pathways. | Prosecutorial policies and trial prospects determine which files survive screening. |

| Court Docket Scheduling | More contested motions, disclosure disputes, and hearings tied to new offence elements. | Courtroom time is finite; calendars, judges, and counsel availability cap throughput. |

| Charter Litigation Precedent-setting | More constitutional challenges around definition, intent thresholds, and expression-adjacent conduct. | Precedent forms sequentially through trial and appeal; timelines are not parallelizable. |

THE SPIN

Sources: CBC News, The Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star

The Left: Criminal law must draw a line around communities

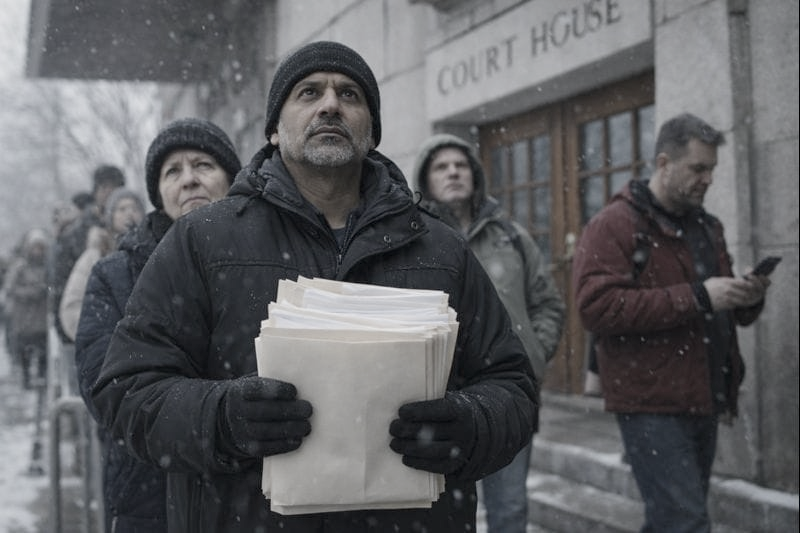

This is what prevention looks like when intimidation has been normalized for too long. People are being harassed and threatened outside synagogues, mosques, schools, and community spaces because extremists learned the system hesitates and looks away.

Hate flourishes when enforcement is slow, fragmented, and politically timid. The state’s obligation is not to referee endless “debate” while people are targeted in real space. Removing political bottlenecks and naming hatred in law is the minimum response to a public sphere that has been deliberately weaponized. The failure was never overreach; it was years of indulgence masquerading as neutrality.

The Right: Definition of a vague law

This is the familiar Ottawa move: expand criminal law first, promise restraint later, and deny responsibility when enforcement turns arbitrary. Turning symbols, intent, and physical proximity into crimes hands enormous discretionary power to police and prosecutors while insulating politicians from the consequences.

Removing Attorney General consent doesn’t make the system fairer; it makes it easier to charge first and justify later. Protest, religious expression, and dissent now exist closer to criminal suspicion, especially for unpopular speakers. When enforcement diverges across provinces, officials will blame “process” while taxpayers fund the confusion and citizens absorb the risk.THE WORLD VIEW

The United States of America

Sources: The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Fox News

U.S. coverage frames Canada’s Combatting Hate Act as a boundary test between public-order policing and First Amendment-style permissiveness. Conservative-aligned outlets interpret the bill as a precedent for expanding “hate” into a tool for regulating protest and religious speech, emphasizing state discretion and selective enforcement risk.

Liberal-aligned coverage tends to frame the same provisions as an overdue response to hate-driven intimidation and violence, with emphasis on protecting targeted communities. Across both lenses, Canada is treated as a governance laboratory whose outcomes are used rhetorically inside U.S. culture-war disputes.

The Global View

Sources: BBC, Financial Times, The Economist

International framing treats Bill C-9 as a Western-democracy governance response to rising hate incidents amid polarization and protest cycles. Coverage often places Canada alongside European restrictions on extremist symbolism, emphasizing institutional legitimacy and public-order maintenance rather than domestic partisan struggle.

The bill is interpreted as a signal about how Canada balances rights language with criminal-law enforcement in a multi-ethnic society. The strategic subtext is reputational: whether Canada can preserve civil-liberties branding while expanding criminal tools that can be applied unevenly across jurisdictions.

WHAT THIS MEANS

Will this change my day-to-day freedom to protest?

Yes.

If a protest tactic involves obstructing or intimidating around specified places, exposure increases. The practical boundary will be defined by police discretion and prosecutorial screening. The same conduct may be charged differently across provinces. The effect will be felt most in high-tension demonstrations near targeted institutions.

Will younger Canadians face a different speech environment than older Canadians did?

Yes.

Codifying hatred and adding symbol-related offences formalizes speech-adjacent criminal risk in ways earlier cohorts did not experience. The constraint is not the text of the law alone but how it is operationalized in charging and plea decisions. Once precedent forms, it becomes the governing reference point for future cases. That creates a durable institutional baseline that outlasts political cycles.

Will this actually reduce hate incidents in the sectors being targeted?

Not in the near term.

Criminal offences change accountability after events, not the underlying drivers of reporting, polarization, or online diffusion. The binding constraint is investigative capacity and evidentiary threshold, which are time-bound. Case throughput depends on resources that cannot be instantly scaled. The short-run effect is more files entering the system, not fewer incidents.

Will enforcement look the same across the West, Ontario/Quebec, and the Maritimes?

No.

Criminal law is federal, but prosecution practice and enforcement prioritization vary by jurisdiction. The removal of Attorney General consent reduces one centralized gate but does not unify provincial charging culture. Local police resourcing and crown policies will shape how often provisions are used. Regional variation is a structural feature, not an implementation bug.

Does this affect Canada’s national interest and reputation abroad?

This reflects a trade-off.

Canada is signalling that public-order protection and community safety can justify tighter criminal-law tools around hate-motivated conduct. The reputational risk is that vague or symbol-based enforcement can be portrayed as politicized speech control. The reputational benefit is alignment with other democracies tightening hate and intimidation enforcement. The long-run outcome will be judged on prosecutorial restraint and consistency, not legislative intent.

THE SILENT STORY

PROSECUTION CAPACITY IS THE REAL GOVERNOR

Public debate fixates on whether Bill C-9 “criminalizes speech” or “stops hate.” The governing force is prosecutorial throughput. This is a Criminal Code regime that only exists when cases move from files to court.

Bill C-9 removes Attorney General consent for hate propaganda charges, but it does not remove the evidentiary sequence that governs prosecutions. Police still need admissible evidence that meets a court-tested definition of hatred, and prosecutors still need a file that can survive charge screening, disclosure, and trial risk. None of those clocks compress because Parliament amended a section.

The delivery pipeline is procedural. Investigations must be built, witnesses must be secured, digital evidence must be preserved, and charges must be approved under provincial prosecution policy. Court scheduling is a throughput constraint: hearings, motions, and trials occur on calendars that do not scale linearly with political urgency. Training is also sequential: investigators, crowns, and judges converge on new offence elements through practice, not press conferences.

Statutory lock-in matters. When Parliament codifies definitions, it also codifies litigation paths: defence challenges, Charter arguments, and appellate clarification. That review sequencing is not parallelizable. Money can fund more people; it does not eliminate the time required for precedent to settle and for enforcement patterns to become predictable.

The incentive blind spot is political time. Bills produce visible action on introduction and passage, while prosecution capacity is invisible until months or years later. Media coverage rewards the announcement phase, not the slow grind of case flow and courtroom throughput. That creates a structural preference for legislative surface area over operational realism.

"Changing the label doesn’t change the docket"

If prosecution capacity remains the governor, the bill’s practical footprint will be defined by selective use, not universal application. The risk is a widening gap between public expectation of immediate deterrence and the slower reality of case maturation. Over time, the system will look stronger on paper while outcomes remain constrained by throughput. The real test will be consistency and restraint across provinces, not the breadth of the statutory language.

SOURCE LEDGER

- Parliament of Canada — C-9 (45-1) LEGISinfo: An Act to amend the Criminal Code (hate propaganda, hate crime and access to religious or cultural places) (2025)

- Parliament of Canada — Bill C-9 — Text of the bill (First Reading) (2025)

- Department of Justice Canada — Canada introduces legislation to combat hate crimes, intimidation and obstruction (2025)

- Department of Justice Canada — Charter Statement — Bill C-9: An Act to amend the Criminal Code (hate propaganda, hate crime and access to religious or cultural places) (2025)

- Statistics Canada — Table 11-10-0054-01 Federal and provincial individual effective tax rates (2025-10-31 release)